Git-Buch jetzt unter CC-Lizenz

Der Verlage Open Source Press hat zum Ende des Jahres 2015 den Betrieb eingestellt, und die Veröffentlichungsrechte der Texte an die Autoren zurückübertragen. Valentin und ich haben uns entschieden, sowohl den Text des Buches als auch die Materialien, die wir für Schulungen verwendet haben, unter einer CreativeCommons-Lizenz zu veröffentlichen. All das könnt ihr ab sofort unter http://gitbu.ch finden. Viel Spaß damit!

Git-Buch, zweite Auflage

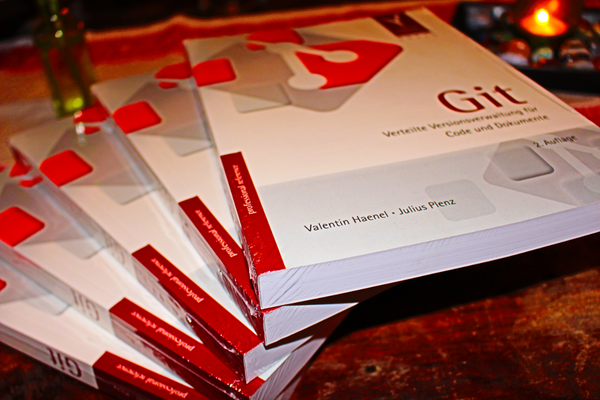

Lange in Planung, aber nun ist sie endlich lieferbar: Die zweite, überarbeitete Auflage des Git-Buchs von Valentin und mir. Da ich gerade nicht am Lande bin, habe ich das Buch noch nicht in den Händen gehalten, aber Valentin hat ein Foto gemacht, denn das Buch trägt das neue Git-Logo auf dem Cover:

Die erste Auflage war Mitte 2011 erschienen. Etwas mehr als drei Jahre später ist diese ausverkauft, und es hat sich so viel in Git verändert, dass es sich lohnt, den alten Text nicht bloß nachzudrucken, sondern aufzuarbeiten (und die Fehler zu korrigieren). Ich zitiere aus dem Vorwort:

Wir haben uns in der 2. Auflage darauf beschränkt, die Veränderungen in der Benutzung von Git, die bis Version 2.0 eingeführt wurden, behutsam aufzunehmen – tatsächlich sind heute viele Kommandos und Fehlermeldungen konsistenter, so dass dies an einigen Stellen einer wesentlichen Vereinfachung des Textes entspricht. Eingestreut finden sich, inspiriert von Fragen aus Git-Schulungen und unserer eigenen Erfahrung, neue Hinweise auf Probleme, Lösungsansätze und interessante Funktionalitäten.

Teils sind die Änderungen nur minimal, und zielen darauf ab, Neulingen

die „moderne“ Syntax der Kommandos beizubringen: Statt git commit

--amend -C HEAD verwendet man nun zum Beispiel git commit --amend

--no-edit, einen Merge bricht man mit git merge --abort ab (statt

mit einem Hard-Reset), und das präferierte Pickaxe-Tool ist -G, nicht

mehr -S (ein subtiler Unterschied!).

Teils werden neue Optionen und Best-Practices (push.default!)

diskutiert, und neue, aber vermutlich wenig bekannte Optionen

vorgestellt (z.B. die neuen Strategie-Optionen der

Recursive-Merge-Strategie, mit denen man durch Whitespace-Unsinn

verursachte Merge- oder Rebase-Konflikte häufig automatisch lösen

kann).

Ein nicht unerheblicher Teil der Änderungen ist der Art, dass man sich als Autor freuen kann: Zum Beispiel haben wir den gesamten Teil über „Subtrees“ im Vergleich zu „Submodules“ umgeschrieben, so dass git subtree verwendet wird, das nun Teil von Git ist. Dadurch fallen mal eben ein Dutzend schwer zu merkender Kommandos weg und werden durch ein Subkommando ersetzt, das eine eigene Man-Page bereithält.

Wir haben über die drei Jahre hauptsächlich sehr positives Feedback zu

dem Text erhalten. Insbesondere wurde von erfahrenen Anwendern häufig

gelobt, dass wir komplexe Beispiele verwenden und „schnell zum Punkt

kommen“. Der größte Kritikpunkt kam sicherlich aus der

Windows-Fraktion: Hier haben sich einige Leute etwas irritiert

gezeigt, wie sehr Unix-zentriert Textgestalt und Inhalte sind. Nach

reiflicher Überlegung haben wir uns entschieden, nicht von diesem

Kurs abzuweichen – insbesondere haben wir die Idee verworfen, eine

Auswahl an GUI-Clients ausführlich zu thematisieren. Wir konnten in

Git-Schulungen besonders mit „EGit“ (Eclipse) einiges an Erfahrung

sammeln, und unser Fazit fällt im Wesentlichen negativ aus: Die Tools

können nicht ansatzweise den Komfort und die Flexiblität des

Original-Git bieten, haben an einigen wesentlichen Stellen Probleme

– EGit kennt z.B. erst seit ein paar Monaten fetch.prune, und es

gibt noch nicht mal einen Knopf dafür im Fetch-Dialog… wie soll man da

effizient mit Branches arbeiten?! – und ändern sich außerdem noch viel

zu schnell, als dass eine gedruckte Dokumentation helfen würde.

Eigentlich sollte die Neuauflage schon Ende des Sommers erscheinen. Dass es nun doch so lange gedauert hat, war vor allem technischen Gründen geschuldet: Die erste Auflage war in LaTeX geschrieben, doch mittlerweile hat der Open Source Press-Verlag auf das eigens entwickelte Publishing-System Textovia umgestellt, das AsciiDoc im Hintergrund verwendet.

Für die initiale Konvertierung von ca. 780 KB LaTeX-Quellcode sind wir dem Verlag sehr dankbar! Allerdings sind uns beim mehrmaligen konzentrierten Durchgehen an diversen Stellen noch übrig gebliebene LaTeX- und Konvertierungsartefakte aufgefallen, und so manchen einfachen LaTeX-Hack konnten wir nicht ohne Probleme in AsciiDoc umsetzen…

Die Umstellung auf das neue Format vereinfacht es immens, eine Print-Version parallel zu mehreren EBook-Versionen zu produzieren; insbesondere ist es aber so, dass nun im Print-Text keine Seitenzahlen mehr referenziert werden, sondern nur noch Abschnitt-Nummern. Wir hoffen, dass sich durch die Konvertierung nicht zu viele neue Fehler eingeschlichen haben.

Neben der Tatsache, dass die neue Auflage moderner und konsistenter ist, bietet sie eine ganz wesentliche Neuerung, die vielfach vermisst wurde: Jedes gedruckte Buch enthält auf der ersten Seite einen Code, mit dem man sich eine PDF-Version des Buches herunterladen kann: So ist das Buch angenehm auf Papier zu lesen, aber gleichzeitig leicht zu durchsuchen.

Clay Shirky: How the Internet will (one day) transform government

git grep

Mit Axel und Frank kam ich

auf Gits eigenes grep zu sprechen. Warum wird die Funktionalität da

gedoppelt und neu programmiert?

Ein Auszug meiner Antwortmail an die beiden, für das Blog mit Links angereichert:

Im wesentlichen leistet git-grep das gleiche wie grep auf allen verwalteten Dateien. ABER es ist, und das war m.E. die Hauptmotivation dahinter, es überhaupt zu schreiben, viel schneller als reguläres grep. (Und reguläres grep zu schlagen ist ja bekanntermaßen schon schwer.)

Zum Beispiel, wenn man im Kernel-Tree greppt. (Alle Kommandos mehrfach ausgeführt, so dass der Cache voll ist.)

$ time grep foo -- **/*.c NO grep foo -- **/*.c &>| /dev/null 17.67s user 0.22s system 99% cpu 17.928 total $ time git grep foo -- **/*.c NO git grep foo -- **/*.c &>| /dev/null 6.17s user 0.31s system 109% cpu 5.888 totalViel beeindruckender wird es noch, wenn man für git-grep das Globbing-Muster erst gar nicht angibt.

$ time git grep foo NO git grep foo &>| /dev/null 0.66s user 0.30s system 342% cpu 0.281 totalOder alternativ ein Globbing-Muster angibt, das aber nicht erst von der Shell expandieren lässt:

$ time git grep foo -- '*.c' NO git grep foo -- '*.c' &>| /dev/null 0.46s user 0.16s system 300% cpu 0.208 total

Also noch mal zusammengefasst: Wenn ich in allen C-Dateien nach "foo" greppe, bin ich mit der Git-Version auf meinem System 17.9/0.208 = 86.05 mal so schnell wie reguläres grep. Anders ausgedrückt: Das eine Kommando dauert, das andere ist fast "sofort da".

Wie das geht? Im wesentlichen ist das auf Multithreading zurückzuführen. (Sieht man ja auch an den CPU-Zahlen: grep bei ca. 100% = eine CPU, git-grep bei >300% = drei CPUs.)

Im Mutltithreading-Modus von git-grep gibt es den Haupt-Thread, der einfach alle Blobs einsammelt, die überprüft werden sollen, und die an acht Threads weitergibt, die dann entsprechend asynchron die Matches durchschauen können, aber trozdem alles in einer sinnvollen Reihenfolge ausgeben. (Details: builtin/grep.c)

Don't believe the hype...?

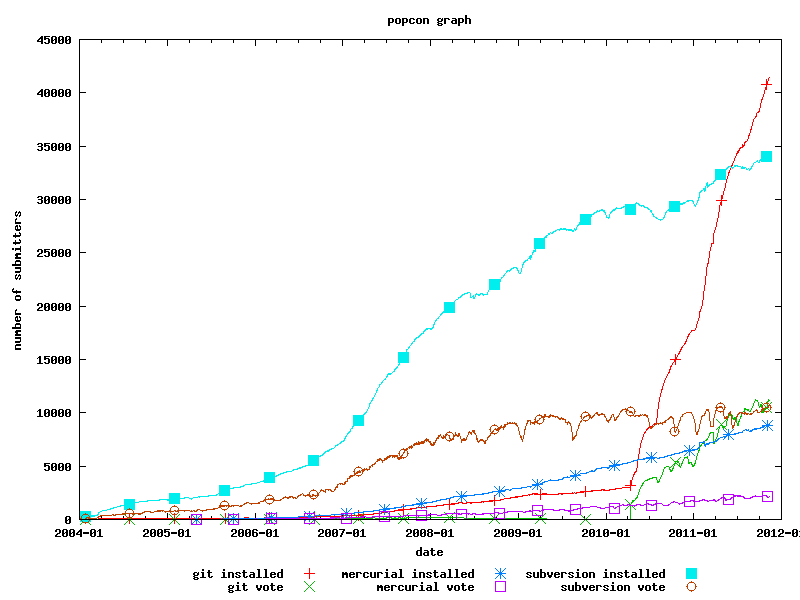

A while ago a link to the following chart from Debian Popcon appeared HN, claiming that "Git is exploding".

I was pretty fascinated by the steep rise of Git's curve. Of course, the statistics are not representative, but they resemble a good set of somewhat typical Debian systems.

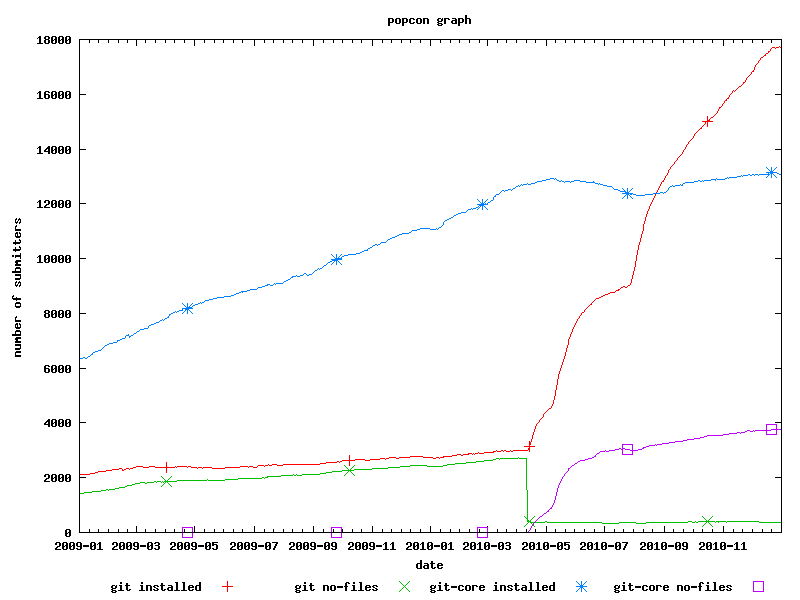

Today, I somehow thought about the graph again – and started investigating. Take a look at this graph:

On April 1st, one of the Git package maintainers uploaded a commit that changed Git's package name to "git" from "git-core". In the graph above you can very well see the steep ascend of of the red line ("git installed"), while at the same time a sudden drop of the "git no-files" package occurs. Slowly, the purple "git-core no-files" follows, indicating that APT replaced git-core with its dummy package that only contains dependencies, no files.

This doesn't explain why the red line's ascend is so steep; however, there must be some relation the package's name change.

Yardsale

Mein guter Freund Valentin zieht in die Schweiz – und verkauft alles, was er nicht mitnehmen kann. (Das scheint mir, abgesehen von Computer, Büchern, Kleidung und Zahnbürste, fast alles zu sein.)

Wenn ihr also an günstigem, gebrauchten Hausrat oder auch an einem großartigen DJ-Set interessiert seid, solltet ihr bei seinem Yardsale vorbei schauen. Ich habe auch schon zwei Sachen gekauft. Die schwarzen Klappstühle werden wunderbar in die Küche passen, sobald sie erst einmal gestrichen ist. ;-)

Übrigens: Das ist der erste Geek-kompatible Yard-Sale, den ich gesehen habe. Die Seite ist autogeneriertes HTML, dessen Markdown-Quellen auf Github verwaltet werden. Entsprechend kann man anhand der Commits (Atom-Feed) verfolgen, was so verkauft wird.

Zum Schluss ein Pro-Tip: Man muss nicht per E-Mail kaufen. Einfach das

Repo auf Github forken, den entsprechenden Artikel in den Sold-Bereich

verschieben, git add -u, committen, und Valentin schreiben. –

Oder wer von euch kann von sich sagen, er habe schon mal per

Pull-Request eingekauft?! – Na eben.

gc via cron on hosted git repos

If you host Git repositories, you might want to implement a cron job that automatically triggers garbage collection on the server side. As a regular user you can't usually access the unreachable objects anyway, so there's no point to keep them.

However, when invoking git gc, Git will pack loose objects together.

This has a huge advantage: When a user clones a whole repository, Git

will compress all objects within a single packfile and transfer it via

the Git protocol. If all the objects are already in one packfile,

there's no overhead in creating a temporary packfile. (If you just

want to get a subset of commits, it's easier for git to "thin out" the

existing packfile, too.)

You can usually see if a computationally expensive temporary packfile

is created if there is a message like remote: counting objects ...

that keeps on counting for a while. For some hosters, this takes quite

some time, because the server is under high load.

I use the following script to trigger git gc every night:

#!/bin/sh

BASE=/var/git/repositories

su - git -c "

cd $BASE

find . -name '*.git' -type d | while read repo; do

cd $BASE/\$repo && git gc >/dev/null 2>&1

done

"

You might want to omit the su part if you create a script that's

executable by the owner of your git repositories itself.

Update: If you don't use cgit's age

files, you'll have all your

repos displaying they were recently changed in the "idle" column. To work

around this, include the following command adter the git gc call:

mkdir -p info/web &&

git for-each-ref \

--sort=-committerdate \

--format='%(committerdate:iso8601)' \

--count=1 'refs/heads/*' \

> info/web/last-modified

svn 1.7

I feel I have a pretty good understanding of Git. Before I came accustomed to it around the end of 2009, however, I had never extensively used version control.

Sure, I used RCS for simple projects; I played around with CVS and bought a book about it; in 2007 I became somewhat accustomed to Mercurial, because the suckless and grml projects used them at the time.

All the time I happened to use Subversion, also for coordinating the work on the book about Z shell.

RCS was simple, but was not at all suitable for collaboration. I thought CVS and Subversion were, alas I never really understood how they worked. As in: why they worked, what was good practice, why you just couldn't seem to run it locally (without client-server architecture).

I happened to just read the release notes of the new subversion 1.7. And, reading the notes, I realize it wasn't me not being attentive or being plain stupid, it's just the interface as well as repository design that was totally messed up. For example:

Subversion 1.7 features a new subcommand called svn patch which can apply patch files in unidiff format (as produced by svn diff and other diff tools) to a working copy.

I mean – what?! This must be such a basic thing – receiving patches via a mailing list and trying to apply them, right? But apparently, there was no need for that since 2000...?

Or consider this great improvement of adding a --diff switch:

svn log can now print diffs

Oh, right. Diffs. In an SCM. Right. Might be of some use.

I'm glad I don't have to use plain SVN any more.

git and the unix philosophy

Good, but slightly older article: Too Smart for Git.

Git follows Linux's philosophy of refusing to protect you from yourself. Much like Linux, Git will sit back and watch you fuck your shit right up, and then laugh at you as you try to get your world back to a state where up is up and down is down. As far as source control goes, not a lot of people are used to this kind of free love.

His conclusion holds true for many other programs also:

The problem isn't that Git is to hard, it's that smart developers are impatient and have exactly zero tolerance for unexpected behavior in their tools.

migrating domains

Today, I migrated all my domains to the new server. While at it, I set up a mirror of my blog repository at http://git.plenz.com/blog/. You could view the pure markdown files there, or see how I messed around with Jekyll stuff.

The sync is called from a post-receive hook with the command:

env GIT_SSH=`pwd`/hooks/blogpush git push -f git@git.plenz.com:blog master

... where blogpush is just a little wrapper to make SSH use the

public key that has access to the repository:

#!/bin/sh

ssh -o ControlMaster=no -i /home/feh/blog.git/hooks/fehblog $@

gitolite and interpolated paths

The Git daemon supports a feature called Interpolated Path. For example, my Git daemon is called like this:

git-daemon --user=git --group=git \

--listen=0.0.0.0 --reuseaddr \

--interpolated-path=/var/git/repositories/%IP%D \

/var/git/repositories

What it does is it translates the request for a git repository before

actually searching for it. When I do a git clone

git://git.plenz.com/configs.git what actually happens is that the Git

daemon will deliver the repository at

/var/git/repository/176.9.247.89/configs.git. That is especially

nice in environments where you share one git daemon for several

people/projects and have sufficient IP addresses.

However, Gitolite doesn't seem to have a config option for this. Now what I did was patch Gitolite so that it'll prepend the repository name with the IP of the network interface the call came through.

This information is available from the SSH_CONNECTION environment variable.

(The patch to gl-compile-conf is needed so that Gitolite will create a

projects.list per virtual host. That way, you can use different

configuration files for each CGit instance, according to your VHost.)

diff --git a/src/gl-auth-command b/src/gl-auth-command

index 61b2f5a..a8d1976 100755

--- a/src/gl-auth-command

+++ b/src/gl-auth-command

@@ -124,6 +124,12 @@ unless ( $verb and ( $verb eq 'git-init' or $verb =~ $R_COMMANDS or $verb =~ $W_

exit 0;

}

+# prepend host's ip address

+# SSH_CONNECTION looks like this: 92.225.139.246 41714 176.9.34.52 22

+# from-ip port to-ip port

+my $connected_via = (split " " => $ENV{"SSH_CONNECTION"})[2] // "";

+$repo = $connected_via . "/" . $repo;

+

# some final sanity checks

die "$repo ends with a slash; I don't like that\n" if $repo =~ /\/$/;

die "$repo has two consecutive periods; I don't like that\n" if $repo =~ /\.\./;

diff --git a/src/gl-compile-conf b/src/gl-compile-conf

index 2d4110f..6f8f0d7 100755

--- a/src/gl-compile-conf

+++ b/src/gl-compile-conf

@@ -577,6 +577,22 @@ unless ($GL_NO_DAEMON_NO_GITWEB) {

}

close $projlist_fh;

rename "$PROJECTS_LIST.$$", $PROJECTS_LIST;

+

+ # vhost stuff

+ my %vhost = ();

+ for my $proj (sort keys %projlist) {

+ my ($ip, $repo) = split '/' => $proj => 2;

+ $vhost{$ip} //= [];

+ push @{$vhost{$ip}} => $repo;

+ }

+ for my $v (keys %vhost) {

+ my $v_file = "$REPO_BASE/$v/projects.list";

+ my $v_fh = wrap_open( ">", $v_file . ".$$");

+ print $v_fh $_ . "\n" for @{$vhost{$v}};

+ close $v_fh;

+ rename $v_file . ".$$" => $v_file;

+ }

}

# ----------------------------------------------------------------------------

With this patch applied, I can git push git.plenz.com:config.git

and it will end up pushing to 176.9.247.89/configs.git, fully transparent

to the user.

N.B.: This strictly is a "works for me" solution. It's not very clean – but I don't plan on properly implementing a config setting. As I said, it works for me. ;-)

Update 2014-09-10: I upgraded to Gitolite v3.6, and it’s different there.

There is a functionality called “triggers” now, which you can activate in the

.gitolite.rc like such: Uncomment the key LOCAL_CODE => "$ENV{HOME}/local",

and insert these two trigger actions:

INPUT => [ 'VHost::input', ],

POST_COMPILE => [ 'VHost::post_compile', ],

Then, place this code under ~/local/lib/Gitolite/Triggers/VHost.pm (you’ll

need to create that directory first):

package Gitolite::Triggers::VHost;

use strict;

use warnings;

use File::Slurp qw(read_file write_file);

use Gitolite::Rc;

sub input {

return unless $ENV{SSH_ORIGINAL_COMMAND};

return unless $ENV{SSH_CONNECTION};

my $dstip = (split " " => $ENV{"SSH_CONNECTION"})[2] // "";

return unless $dstip;

return if $dstip eq "127.0.0.1";

my $git_commands = "git-upload-pack|git-receive-pack|git-upload-archive";

if($ENV{SSH_ORIGINAL_COMMAND} =~ m/(?<cmd>$git_commands) '\/?(?<repo>\S+)'$/) {

$ENV{SSH_ORIGINAL_COMMAND} = "$+{cmd} '$dstip/$+{repo}'";

}

}

sub post_compile {

my %vhost = ();

my @projlist = read_file("$ENV{HOME}/projects.list");

for my $proj (sort @projlist) {

my ($ip, $repo) = split '/' => $proj => 2;

$vhost{$ip} //= [];

push @{$vhost{$ip}} => $repo;

}

for my $v (keys %vhost) {

write_file("$rc{GL_REPO_BASE}/$v/projects.list",

{ atomic => 1 }, @{$vhost{$v}});

}

}

1;

cgit and setuid

I'm still in the process of setting up my new server. Today, I migrated the Git repositories. I wanted a more secure setup, that is I don't want my web server to be able to read the repositories. (It spawns CGit, which has to read them somehow.)

So I created all repositories below /var/git/repositories, such that

they are only readable by the system user "git".

However, that presents a problem to the CGit CGI: It cannot access the

repositories any more. My first approach was: Just chown git.git

/usr/lib/cgi-bin/cgit.cgi and set the setuid bit on it.

But, alas, that will only make the CGit binary run with effective user ID "git". What's needed to actually access the files is a real user ID "git".

The only way to set the real user ID is to call setuid() with

effective root privileges. So I created a wrapper that

- searches for git's user ID

setuid()s to that ID (real an effective)- executes the actual CGit CGI

That's what I came up with:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <pwd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

struct passwd *p;

uid_t git_uid = 0;

while((p = getpwent()) != NULL) {

if(strcmp(p->pw_name, "git"))

continue;

/* got user "git" */

git_uid = p->pw_uid;

}

endpwent();

if(!git_uid)

return 1;

setuid(git_uid);

execv("/usr/lib/cgi-bin/cgit.cgi", argv);

return 0;

}

Provide it with a Makefile... (beware, use real tabs!)

default:

gcc -Wall -o cgit-as-git.cgi cgit-as-git.c

install:

install -o root -g root -m 4755 cgit-as-git.cgi /usr/lib/cgi-bin

... and change the Lighttpd configuration accordingly:

$HTTP["host"] == "git.plenz.com" {

setenv.add-environment += ( "CGIT_CONFIG" => "/etc/cgit/plenz.com.conf" )

alias.url = (

"/cgit.css" => "/usr/share/cgit/cgit.css",

"/cgit.png" => "/usr/share/cgit/cgit.png",

"/cgit.cgi" => "/usr/lib/cgi-bin/cgit-as-git.cgi",

"/" => "/usr/lib/cgi-bin/cgit-as-git.cgi",

)

cgi.assign = ( ".cgi" => "" )

url.rewrite-once = (

"^/cgit\.(css|png)" => "$0",

"^/.+" => "/cgit.cgi$0"

)

}

Done! Lighttpd can now call CGit as if it was a "usual" binary, but it will get wrapped and get the real and effective user ID of the system's user "git".

N.B.: If you want to use the wrapper as well, you might want to change

the (hard coded) user name "git" and the binary (see execv call).

Git User's Survey

The Git User's Survey is up from now until the beginning of october. Take part!

Das Gitbuch ist da!

Gestern frisch aus der Druckerei, jetzt hier: Heute sind meine Belegexemplare des Git-Buches angekommen! Damit ist es jetzt auch im Handel verfügbar.

Es ist ein wirklich tolles Gefühl, ein so großes Projekt abgeschlossen zu haben und das Ergebnis in den Händen zu halten. – Jetzt erst mal abwarten, wie so die Rückmeldungen ausfallen. ;-)

git: find absolute path to tracked file

If you need to name a blob by name, you can't trust Git to honor the

current working directory. If you are in a subdir, git show

HEAD^:file won't work unless you prepend the subdirectory name.

But there's a sort of basename for absolute paths within a Git repo:

git ls-tree --name-only --full-name HEAD file

This honors $PWD and thus returns a pathname that's unique across

the repository. You can build a simple "diff to previous version"

script with this now:

#!/bin/sh

test ! -z "$1" || exit 1

temp=${1%.*}.HEAD^1.$$.${1#*.}

fullpath=`git ls-tree --name-only --full-name HEAD^ $1`

test ! -z "$1" || exit 2

echo "extracting '$fullpath' from HEAD^..."

git show HEAD^:$fullpath > $temp

vim -fd $1 $temp

echo "cleaning up..."

rm $temp

This can act as a simplified mergetool when you just want to

review changes made to some file.

git: forget recorded resolution

Git's rerere is immensely useful. However, if you erroneously

record a wrong conflict resolution, it's not entirely clear how to

delete it again. The preimage file is stored under

$GIT_DIR/rr-cache/some-sha1-sum/preimage, which is not a convenient

place to look for that one wrong resolution if you have hundreds of

them. ;-)

However, v1.6.6-9-gdea4562 introduced rerere's forget subcommand,

which was not documented until recently (v1.7.1.1-2-g2c64034). So

when rerere replays a wrong resolution onto your file, simply use git

rerere forget path/to/file to forget the wrong resolution.

To (temporarily) replace the resolved version with the originial

version containing conflict markers, use git checkout -m --

path/to/file. You can then issue a git rerere to replay the

resolution again.

criss-cross subtree merges

Note to self: It is bad to rely on Git's magic of finding out whether you can fast-forward when doing a merge. The more clever way is to explicitly state what you want to do with aliases:

nfm = merge --no-ff # no-ff-merge

ffm = merge --ff-only # ff-merge

I stumbled upon this today when I played around with subtree merges.

Strangely, the results with the strategy subtree were not the same

as with recursive's subtree=path option:

$ git merge -s recursive doc

$ git merge -Xsubtree=Documentation doc

Turns out that – in the special case I had created – Git could fast-forward the branch although it was a subtree merge, effectively ignoring any strategy option. Duh. I had already read, understood and tried all the tests related to merging before I had figured that out.

git tracking branch management

There are different approaches 'round the net on how to deal with git remote tracking branches in an effecient way. Some people have written Ruby gems (uggh) that introduce lots of not-so-intuitive git subcommands to manage all kinds of tracking branches.

In recent versions of Git however, I have no need for these scripts. I can live with the following aliases:

lu = log ..@{u}

ft = merge --ff-only @{u}

track = branch --set-upstream

To track a branch, I enter git track master origin/master, for

example. (By the way, if you create a new branch and want to push it

to a remote, use push -u – it will automatically set up your

current branch to track the remote branch you just created.)

Then, my regular workflow looks like this:

$ git remote update # fetch changes

$ git lu # log ..upstream -- review changes

$ git ft # ff tracking branch -- integrate

The key here is using @{u}, which is a short form of @{upstream},

a reference to the upstream branch (that is, the branch your HEAD is

tracking). This special notation first appeared in Git 1.7.0.

If you're not sure about the current status of your branches and what

they are tracking, simply use git branch -vv. You'll find the

tracking information in brackets just before the commit description.

Upgrading to Gitolite and CGit

I finally found some time to update the git version used on my server. It's running a 1.7.1 now, which is just slightly better than the previous 1.5 version. ;-)

Debian package maintainers bother me again, though. The simply erase

the git user and put a gitdaemon user in it's place, without

asking for confirmation. Will probably happen with the next upgrade,

too...

Now, having a recent git version enables me to set up gitolite instead of the old gitosis. Setup is easy, straight-forward and described in many places.

I used this script to convert my existing gitosis.conf to match

gitolite's syntax; I noticed a major hiccup though: setting a

description automatically enables gitweb access. I had to read

the source to find this out, because I couldn't remember it from the

docs and it didn't once cross my mind that you could actually want

the behaviour to be like that. – As in, you could just describe

a project without wanting to make it public – no?

However, with gitolite, I can finally use CGit too (because only

gitolie produces a repositories.list which is in the format that

CGit understands, ie. without description appended to the lines).

So now the repository page is all new and shiny. See, for example, this side-by-side diff. Nice, and faster than Gitweb.

Integrating CGit with Lighttpd was another two-hour fiddle-try-fail-repeat session. I finally came up with this snippet:

$HTTP["host"] =~ "^git\.(plenz\.com|feh\.name)(:\d+)?$" {

alias.url = (

"/cgit.css" => "/usr/share/cgit/cgit.css",

"/cgit.png" => "/usr/share/cgit/cgit.png",

"/cgit.cgi" => "/usr/lib/cgi-bin/cgit.cgi",

"/" => "/usr/lib/cgi-bin/cgit.cgi",

)

cgi.assign = ( ".cgi" => "" )

url.rewrite-once = (

"^/cgit\.(css|png)" => "$0",

"^/.+" => "/cgit.cgi$0"

)

}

It's important here that you noop-rewrite the CSS and PNG file to

make Lighty expand the alias. Also, rewriting to an absolute filepath

won't work; that's why the cgit.cgi aliases have to appear twice.

add -p for new files

If you have a file that's unknown to git (ie., it appears in the

"untracked" section of git status), and you want to add only part of

the file to the index, git won't allow it: No changes.

Instead, mark the file for adding, but without adding any actual line:

$ git add -N file

$ git add -p file

-N is short for --intent-to-add and does just that: Create an

index entry with an empty content field.

Strip whitespace on rebase

Normally, I use the following line in Git's pre-commit hook:

git diff --cached --check || exit 1

This makes a git commit abort if there are any whitespace-related

errors. However, if you have code that already has whitespace issues,

you can simply pass an option to git rebase to automatically correct

them:

git rebase --whitespace=fix reference

N.B.: Rebase just passes this argument to the git apply command.

Automatic screenshot processing

Cut out window borders and application bars from screenshots automatically: note down some corner points (in Gimp), then use ImageMagick:

for f (*.png) { convert -crop 975x559+2+30 $f $f; }

Task done!

NB: This command replaces file contents. So when not

sure about the numbers, append some extension to it and view the

results first. Or, simply kepp the images in a git controlled

directory. That way, a simple git reset -- . will restore your

previous images if you added them in the first place.

First post with posting tool

This is my first post with a custom shell script. It automatically adds a YAML header on top of new posts, starts an editor on it and later converts the title to a nice filename.

Eventually, the script adds and commits the new post to the git repo and pushes the result. "Recovering" is supported – sort of. ;-)